MEDIATRIX OF GRACE

In that day I will raise up the booth of David that is fallen…

the mountains shall drip sweet wine,

and all the hills will flow with it.

Amos 9, 11, 13

And in that day the mountains shall drip sweet wine…

and all the stream beds of Judah shall flow with water;

and a fountain shall come forth from the house of the Lord.

Joel 3, 1

AND the third day, there was a marriage in Cana of Galilee: and the mother of Jesus

was there. And Jesus also was invited, and his disciples, to the marriage. And the wine

failing, the mother of Jesus saith to him: They have no wine. And Jesus saith to her:

Woman, what is that to me and to thee? my hour is not yet come. His mother saith to the

waiters: Whatsoever he shall say to you, do ye. Now there were set there six water-pots of

stone, according to the manner of the purifying of the Jews, containing two or three

measures apiece. Jesus saith to them: Fill the water-pots with water. And they filled them

up to the brim. And Jesus saith to them: Draw out now, and carry to the chief steward of

the feast. And they carried it. And when the chief steward had tasted the water made wine,

and knew not whence it was, but the waiters knew who had drawn the water; the chief

steward calleth the bridegroom, And saith to him: Every man at first setteth forth good

wine, and when men have well drunk, then that which is worse. But thou hast kept the

good wine until now. And saith to him: Every man at first setteth forth good wine, and

when men have well drunk, then that which is worse. But thou hast kept the good wine

until now.

John 2, 1-11

And the wine failing, the mother of Jesus saith to him:

They have no wine.

Catholics hold the belief that Jesus Christ serves as the sole Mediator between God and humanity, as indicated in 1 Timothy 2:5. This concept underscores that Jesus is responsible for redeeming the world and reconciling all of humanity to God by offering his life as a ransom for sin, highlighted in 1 Timothy 2:6. While Jesus is recognized as the principal mediator in his human experience, this does not exclude the faithful from playing a role in mediation or intercession. Believers are encouraged to pray and make sacrifices with the intention of salvation for all and to promote knowledge of the truth, a theme found in 1 Timothy 2:1-4.

The concept of mediation in salvation within Christianity is rooted in the belief that Jesus serves as a primary mediator. However, it is essential to recognize that Christians are also called to actively participate in this mediation as members of His Mystical Body. This role is bestowed upon them as adopted children of God, allowing them to partake in Christ's divine nature, as referenced in 1 Peter 2:5 and 2 Peter 1:3-4.

In his role as the head of the Mystical Body, Christ intercedes on behalf of humanity not from his divine nature, but through his humanity. The Letter to the Hebrews elaborates on this, describing Christ as our High Priest who perpetually intercedes for us within the heavenly sanctuary. This intercession serves to continually present His sacrifice from Calvary, which was foreshadowed during the Last Supper and is re-presented during the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. Through this ongoing process, daily sins are atoned for, emphasizing the connection between Christ's sacrifice and the spiritual life of believers.

Exegete Manuel Miguens highlights that verse 5, when translated from Greek, conveys the message: “There is one and the same God for all, and there is one and the same mediator for all.” This interpretation underscores that both Jews and Gentiles are recipients of the Father’s merciful love and the Son’s obedient act of atonement. The Greek term used for “one” in this verse is heis (εἷς), which suggests a “sameness of function,” indicating commonality or universality. In other words, Jesus is the one and the same mediator for the Jews and Gentiles. This choice of words is significant. Had the Apostle Paul intended to imply that there is only one mediator in the entirety of salvation's framework, he would have likely used the term monos (μόνος). This word implies "only" in the context of exclusive uniqueness rather than indicating a shared function.

In discussions of salvation, Paul highlights Jesus as the primary mediator between God and humanity, encompassing both Jews and Gentiles. Jesus's role as the mediator is rooted in His unique ability to redeem all of humanity from sin and death (V. 6). Unlike any other individual, Jesus intercedes for us before God, leveraging His divine nature and equal status with the Father. It is important to understand that while individuals are encouraged to intercede for others (vv. 1-4), particularly through the sacrament of baptism, their role is secondary and supportive. This intercessory participation is realized as members of Christ’s Mystical Body, relying on His merits to fulfill this calling.

In the Old Testament, Moses played a crucial role as the mediator of the covenant between God and the Israelites. This foundational agreement, which established the relationship between God and His chosen people, finds its ultimate fulfillment in the New Testament through Jesus Christ. By His sacrificial death and resurrection, Jesus inaugurated the New Covenant, which is central to the Christian faith and essential for the forgiveness of sins. While all baptized Christians are offered the opportunity to engage with this grace, participation is not automatic. Instead, God invites them to actively partake in His grace and love as members of Christ’s Mystical Body. This invitation emphasizes the call to collaborate with God in His mission, as his “fellow workers” (1 Cor 3:9).

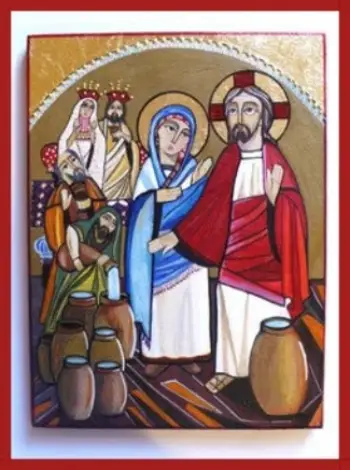

Jesus serves as the primary mediator between God and humanity, playing a central role in the plan of salvation. However, he is not the only figure in this mediatory role. All baptized Christians, through the merits of Christ, can also engage in the process of mediation. As members of a royal priesthood, they can intercede for others through their prayers and personal sacrifices, which can generate actual graces that contribute to the salvation of others. Additionally, in the Gospel account of the Wedding Feast at Cana, Mary, the mother of Jesus, is depicted as an effective mediator who conveys her Son’s grace in accordance with his unique covenant.

St. John’s theology is often regarded as deeper and more complex than that of the authors of the Synoptic Gospels, which contributes to the unique mystical quality of his Gospel. In the narrative of the wedding feast at Cana, John portrays Mary as a universal mediator of grace, highlighting her role alongside her Son in His redemptive mission through allegorical representation. In Scriptural contexts, grapes or other vine fruits symbolize God's grace or favor toward humanity and the concept of spiritual regeneration. Conversely, the absence of grapes can represent a fall from God's grace and a loss of true happiness, which is attainable only through a life governed by divine principles. The scenario of a vineyard stripped of grapes serves as a metaphor for the absence of grace and holiness in the lives of individuals who have turned away from God and embraced false idols, ultimately reaching a state of spiritual impoverishment.

Spiritual famine occurs when individuals lose their faith and trust in God, making them susceptible to deceptive influences. This vulnerability can lead to the erosion of one's spiritual integrity, which is essential for a fulfilling divine life. The prophet Micah poignantly illustrates this concept by lamenting his state, comparing the Israelites to summer fruit that has been harvested and expressing a deep longing for spiritual nourishment: “Woe is me! For I have become like the summer fruit that has been harvested, like the grapes that have been gathered; there is no cluster to eat, no ripe fig that my soul desires.” Similarly, in Obadiah 1:5, it is stated that even robbers, when they come, would only take what they need for themselves, leaving some behind, highlighting how a lack of spiritual sustenance can lead to a more profound sense of loss and emptiness.

The concept of grace plays a significant role in the well-being of the soul. When deprived of grace, individuals often experience suffering, calamity, and misery, which can lead to a profound sense of despair and destruction. In contrast, divine grace provides joy and uplifts the soul through the manifestation of God's love, showering it with numerous blessings. Divine grace acts as a purifying force, cleansing the soul of darkness and negativity that can lead to unhappiness and despair. It invigorates and sustains the soul, offering nourishment in the form of true happiness and absolute peace, even in the face of challenges and hardships. This idea is echoed in the biblical text of Psalm 104:14-15, which highlights the connection between divine provision and human well-being: "You cause the grass to grow for the livestock and plants for man to cultivate, that he may bring forth food from the earth and wine to gladden the heart of man, oil to make his face shine, and bread to strengthen man’s heart." This scripture underscores the role of divine grace in fostering a fulfilling and joyful existence.

God's grace is truly transformative, playing an essential role in our journey toward holiness and righteousness. It empowers us to cultivate a more fruitful spiritual life and embrace the gift of eternal life in God's presence—our ultimate source of joy and inner peace. The words of the prophet Jeremiah remind us to keep our faith strong and to continuously seek God's grace, especially in times of struggle after making mistakes. He inspires us with the promise that “Again you shall plant vineyards on the mountains of Samaria; the planters shall plant and enjoy the fruit” (31:5), highlighting the renewal found through God's forgiveness.

Moreover, the exile of the ancient Hebrews anagogically illustrates humanity's fallen nature due to original sin, but it also emphasizes the beautiful possibility of reconciliation with God. Through the sacrifice of Jesus on the Cross, we can restore our connection to the Divine and live a life rich in grace. This powerful narrative encourages us that no matter our past, we can always turn back to God and cultivate a vibrant relationship with Him, filled with promise and hope.

You have heard of the stewardship of God’s grace

that was given to me for your benefit.

Ephesians 2, 3

In the Gospel of John, an interesting exchange occurs between Jesus and his mother, Mary, where Jesus says, “What is that to us, woman?” This phrase may initially appear to indicate a dismissive attitude toward Mary's concerns in less accurate modern translations. However, a deeper examination reveals that both Mary and Jesus are united in their commitment to the salvation of Israel and the Gentiles. The original Greek phrase used by Jesus is “te emoi kai soi,” which translates to “what to thee and to me.” This expression reflects a close personal relationship between them, emphasizing their shared interests and concerns. Furthermore, the term "woman," translated from the Greek word “gynai,” is a respectful and polite form of address. Yet Jesus' use of this title carries theological significance, suggesting a meaning that transcends mere politeness. This interaction highlights the complex dynamics of their relationship and the overarching soteriological themes of the Gospel.

The expression that closely parallels the phrase “What is that between friends (mother and son)?” in English is found in the Hebrew New Testament as “mah-liy walak isah,” which translates to “what is there to me and you?”. This phrase serves as a polite way of asking, “What would you have me do, woman?” and suggests that the speaker is already aware of the woman's desires. In this context, Jesus is subtly posing a rhetorical question to his mother, indicating that her concerns about the wine are not trivial. His inquiry, which can be interpreted as “What concern is this matter of the wine to us?” reflects a deeper understanding of the significance of the wine in relation to Jewish eschatology. Both Mary and Jesus recognize that the issue at hand transcends practical matters, signifying something of spiritual significance. Thus, what concerns Mary indeed holds importance for Jesus as well, demonstrating an interconnectedness in their roles.

In this passage, Jesus addresses his mother, prompting her to consider how the situation may also relate to him. This interaction signifies her involvement in his divine mission of salvation, indicating that she must accept the necessity of participating in his forthcoming actions. This pivotal moment marks a profound transformation in their relationship, as Mary will have to come to terms with the reality of losing her son and witnessing his suffering and death at the hands of those who do not appreciate him. Despite the seriousness of the circumstances, a deep mutual concern exists between Jesus and Mary that transcends their familial bond. Mary understands that her son is on the verge of commencing his public ministry and anticipates that he will perform a miracle. This moment signifies the beginning of a significant phase in Jesus' life, and both mother and son are poised to face the challenges that lie ahead.

In this significant event, Jesus' mother recognizes that it is time for him to commence his public ministry, which aims to provide spiritual benefits and salvation to Israel and all of humanity. It is noteworthy that Jesus sought his mother's affirmation of her support for this mission, particularly considering the sorrow that would eventually accompany it. Mary's concerns were valid and aligned with Jesus' divine will, which was in harmony with his human intentions. The miracle that followed was inevitable, as it marked the appointed hour for Jesus, serving as a sign of what was to come, particularly in relation to the Cross. While Jesus had no further words to add at that moment, Mary, assuming the role of head steward on behalf of the bridegroom and host, directed the servants with the important instruction: “DO WHATEVER HE TELLS YOU.” This directive emphasizes the significance of obedience to Jesus and the manifestation of his divine authority.

Expecting her Son to perform that first miracle that will inaugurate his public ministry on earth in the shadow of the Cross, Mary faithfully approaches him with her tacit request. Here, we must note the rich symbolism in this circumstance, where the lack of wine renders the wedding feast a disaster in ancient Jewish culture. The wine is evocative of the blood of the new and everlasting Covenant (Mt.26:27-28). The elements of wine and blood are identified at our Lord’s paschal supper with his apostles on the eve of his passion and death at the Jewish Passover.

The wedding feast at Cana serves as a significant symbol of the eschatological wedding of the Lamb, representing the union between the Divine Bridegroom and His Bride, the Church. This union is realized through the sacrificial shedding of His blood, as noted in Revelation 19:6-9. Mary, the mother of Jesus, played a crucial role as a mediator of divine grace for humanity when she accepted her divine calling at the Annunciation (Lk 1:38). Her continued intercession was evident when she encouraged Jesus to commence His mission, a journey that ultimately led to His sacrificial death. This act was pivotal for the atonement of the world's sins, resulting in the redemption of humankind.

Thus, in the context of the wedding at Cana, Mary plays a significant role as a steward in the distribution of an extraordinary wine, symbolizing her concern for the Bridegroom. This wine represents the blood of her Son, which far surpasses the offerings of goats and bulls from the Old Covenant. By urging her Son to perform his first miracle, Mary demonstrated a willingness to sacrifice her maternal rights to address a matter of greater importance than simply providing wine for a family celebration. Mary’s request is seen as an expression of her faith and charity, and it sets the stage for a pivotal moment in Christian theology. This event marks the commencement of the wedding feast of the Lamb, underscoring the intimate relationship between Christ and the Church. The Church, referred to as the bride, prepares to celebrate this union in the heavenly kingdom (Rev. 17:7,9).

In the narrative of the wedding feast, the Gospel of John presents Mary as a factual mediator, not unlike Abraham and Paul in their respective roles, who is actively involved in mediating with her divine Son, Jesus. This portrayal aligns with the tradition of the nascent church regarding Mary, depicting her as a universal mediatrix who channels graces through her intercession, prayers, and maternal sacrifices. According to this perspective, all graces are meant to flow through Mary due to her unique role as the mother of Jesus. The text specifically notes, “the mother of Jesus” was present at the event, highlighting her essential role in this context.

Every man has received grace,

ministering the same to one another:

as good stewards of the manifold grace of God.

1 Peter 4,1

In the context of Christian theology, the role of the Virgin Mary holds significant importance within the Mystical Body of Christ. Jesus has conferred a distinctive honor upon his mother, allowing her to be recognized as a chief participant in his mediation for humanity's salvation (1 Cor 12:20-23). This perspective is reinforced by the belief that Jesus did not intend to act independently in the Divine work of salvation; rather, he chose Mary to collaborate with him in the mission of redeeming souls through the grace that he offers. All faithful disciples of Christ, referred to as “stewards of grace,” are called to participate in this mission according to the spiritual gifts they receive from the Holy Spirit. The concept of Divine Maternity is considered the greatest gift for any follower of Christ, as it directly pertains to the hypostatic union of Christ’s incarnation.

If Mary did not play a central salvific role in her Son’s first and most significant miracle—one with profound eschatological significance and initiated by her request—John would not have included her involvement in the narrative leading to its climax. He could have simply stated: “On the third day, a wedding took place at Cana in Galilee. Jesus was there, along with his mother, Mary, and his disciples, who had also been invited to the wedding (vv. 1-2). …Jesus noticed (not his mother) that the wine had run out. Nearby stood six stone water jars… Jesus said to the servants (without Mary having first instructed them to obey her Son), ‘Fill the jars with water…’” (vv. 6-11). Instead, we find Mary mediating on behalf of the wedding guests as a key actor (vv. 3-5).

The actions of Mary in this narrative are not merely incidental; everything in Scripture and well-crafted literature is intentionally placed, including the significance of the wine that runs out during the event. This wine represents more than just a beverage; it holds spiritual meaning within the context of the story. Mary is a central figure in this account, playing a significant role that contributes to the overarching theme of the New Covenant established through her Son's sacrificial act. The sacrificial aspect of this narrative can be traced to the Last Supper, where Jesus initiates a new nuptial covenant that culminates with his sacrifice on Calvary, epitomized in his declaration, "It is finished!" (Jn 19:30). During the Crucifixion, Mary stands sorrowfully at the foot of the Cross, having completed her crucial role in the narrative. This moment marks her transition into a new role as the Mother of the Church, symbolizing her position as the Matriarch of the New Covenant, which signifies a new era of grace for humanity.

Thus, God Himself implicitly tells us something deeply important about Mary through the literary technique of His co-author (sensus plenior). Our Blessed Lady is a central character in the story and has a significant role. She is, in fact, first mentioned as being present at the wedding feast, followed by Jesus and his disciples. This is because the Evangelist wishes to draw our attention to Mary before he proceeds with the miracle that is performed by Jesus at his mother’s behest. Mary has an essential role in performing her Son’s first and most crucial miracle, which serves as a sign that the Divine Bridegroom is about to consummate His marriage covenant with His bride, Israel, and all peoples of the world. As the mother of our Lord, she is giving her Son away in marriage.

If Mary’s presence were not seen as deeply meaningful in terms of her moral contribution to the Divine dispensation of grace, it stands to reason that the author would not have emphasized her role in the pivotal events leading to the miracle and the commencement of her Son’s public ministry, which would ultimately unfold in the shadow of the Cross. This literary protocol underscores the intentionality behind her inclusion. Mary’s active participation not only highlights her significance within the narrative but also reflects the nascent church’s understanding of her role as a co-participant in the redemption of humanity, showcasing her collaboration with the Son in the divine plan of salvation. Indeed, her involvement is not merely incidental but an integral aspect of the theological framework that supports the story of redemption from John’s perspective.

Traditionally, Mary has been revered as the Mediatrix of Grace, a role reflecting her integral position in the economy of salvation. As we have seen, in the Old Testament, various agricultural symbols, particularly the fruit of the vine, which includes grapes, olives, and figs, embody God's grace and the inherent need for spiritual rejuvenation. The prophet Micah poignantly captures this sentiment, lamenting, “Woe is me! For I have become as when the summer fruit has been gathered, as when the grapes have been gleaned; there is no cluster to eat, no first-ripe fig that my soul desires” (Micah 7:1). This metaphor illustrates not only personal desolation but also symbolizes the collective fall from divine grace experienced by the Israelites during their exile. Their dislocation serves as an allegory for humanity’s universal yearning for redemption and the restoration of one’s relationship with God, highlighting an enduring need for grace that transcends time and culture.

Shall not Zion say:

This man and that man is born in her?

and the Highest himself hath founded her.

Psalm 87, 5

During a traditional week-long family wedding ceremony, the wine typically ran out during the fifth stage known as the chuppah, or "canopy." This ceremonial element consists of a decorated cloth held above the couple, symbolizing their new home together. The chuppah is often placed outdoors, under the open sky, reflecting the biblical blessing given to Abraham that his descendants would be "as the stars of the heavens." As part of the ceremony, the groom is escorted to the chuppah by his parents while wearing a crown and a white robe, known as a kittel. This attire signifies a fresh start for both the bride and groom, as they come together to form a new entity, free from past sins. The bride, accompanied by her parents, walks to the chuppah as a cantor performs selections from the Song of Songs, which serves as a metaphor for the union between Christ and the Church in Christianity. Additionally, during this moment, the groom offers a prayer for his unmarried friends to find their true partners in life.

During a traditional Jewish wedding ceremony, the bride is celebrated with a joyful procession to the chuppah, where she circles the groom seven times, accompanied by her mother and future mother-in-law. Meanwhile, the groom engages in prayer. To symbolize the unification of the two families, the groom's mother participates in a dance with the bride and her parents. The bride typically wears a crown and a gown made of pure white linen, drawing parallels to the imagery of Christ’s bride in the Book of Revelation. Once under the chuppah, a respected Rabbi or family member offers a blessing over a cup of wine. This blessing expresses gratitude to God for the laws that uphold the sanctity of family life and the Jewish community. Following the blessing, the bride and groom partake in the wine, which serves as a symbol of life.

In the context of a traditional Jewish wedding, the Gospel of John presents a profound depiction of Mary as she interacts with the family of her son’s bride, symbolizing the Church. This significant moment occurs during a celebration where the bride prepares to leave behind her past transgressions and steps into a transformative new journey by uniting with the groom, an act that signifies spiritual rebirth and renewal. The wine served during this celebration carries layers of meaning; it not only represents the joy and vitality of life but also signifies the transformed essence of Jesus’ blood, which is identified as the source of eternal life in communion with God. To fully appreciate the depth and meaning of this Gospel narrative, it is essential to interpret it through the Jewish perspective of the Evangelist, recognizing its roots in Jewish culture and traditions. This understanding illuminates the story’s rich symbolism and the importance of covenant, community, and divine relationships inherent in the Jewish faith.

In Jewish eschatology, there is an expectation that the Messiah will once again bring manna from heaven and oversee the sacrificial rituals involving the Bread of the Presence and miraculous sacrificial wine. These rituals are believed to address the original sin of Adam and Eve within a restored Temple in Jerusalem, following the order of the priest-king Melchizedek, an ancestor of David. Throughout the periods of the First and Second Temples, priests conducted unbloody sacrifices to achieve temporal forgiveness of sins, utilizing holy bread and wine during Sabbath services. The Bread of the Presence, also referred to as the Face of God, was housed in a tabernacle within the Temple's sanctuary. This bread symbolized God's merciful love for the people of Israel and represented His providential presence among them.

Mary's involvement in the events surrounding the wedding at Cana highlights her significant role in the early Christian community and her unique collaboration with Jesus in the process of redemption, particularly through her identity as His mother. The Gospel of John refers to her simply as "the mother of Jesus," which emphasizes the respect accorded to her maternal role within the context of grace. During the wedding ceremony, the groom's mother would traditionally dance with the bride and her family to symbolize the joining of their families. In this context, Mary assumes a mediatory role, representing a connection between Christ and His Church. Through her, the faithful are formally united with Jesus at the wedding banquet in the kingdom of heaven.

And the wine failing, the mother of Jesus saith to him:

They have no wine. And Jesus saith to her: Woman, what is

that to me and to thee? My hour is not yet come. His mother saith

to the waiters: Whatsoever he shall say to you, do ye.

John 2, 3-5

The narrative of The Wedding Feast at Cana is an intriguing literary work, where every character, including the servants, plays a significant role. After their initial mention, the disciples do not have further dialogue, which prompts an interesting examination of the servants’ portrayal. In the account, Mary instructs the servants with the phrase, “Do whatever he tells you” (Jn 2:5). Notably, Catholic biblical scholar Dr. Edward Sri, in his book Walking with Mary (Crown Publishing, 2017), emphasizes that the Gospel writer John intentionally chooses the term diakonois, rather than the more common Greek word duolois for "servants." The word diakonois is associated with true discipleship throughout the New Testament. For instance, in John 12:26, Jesus states, “If anyone serves (diakonei) me, he must follow me; and where I am, there shall my servant (diakonoi) be also.” This choice of terminology indicates that John presents Mary not only as the mother of Jesus but as the mother of all His disciples, symbolizing the Church (the bride of Christ). In this role, her primary message to all believers is clear: “Do whatever he tells you.”

In the context of Christian theology, the role of Mary, the mother of Jesus, is emphasized as a nurturing figure and spiritual guide for believers. The Gospel of John illustrates this through the narrative of the Wedding Feast at Cana, where Jesus refers to her as His "mother" rather than by name. This choice of wording highlights a deeper significance, indicating Mary’s dual role as both the physical mother of Christ and a spiritual mother to His disciples. This moment occurs just before Jesus completes the New Passover meal, further linking Mary’s significance to themes of obedience and faithfulness. John's Gospel is often noted for its mystical qualities, diverging from the more straightforward accounts found in the Synoptic Gospels. The allegorical nature of the Wedding Feast at Cana invites readers to reflect on the broader implications of Mary’s maternal influence on the faithful.

When Jesus asks his mother about the concern about the wine, he makes a subtle reference to significant events such as the Last Supper and Calvary, where he acknowledges Mary as the Mother of the Church. This moment during the wedding feast can be understood as a foreshadowing of the New Jerusalem, which descends from heaven through the new and everlasting covenant—the spiritual union between Christ, the Bridegroom, and the Church, his bride. For Mary to fulfill her role, she must formally align her Son with this new covenant, establishing herself as the mother and Advocatrix of grace through the merits of her divine Son. This act of mediation represents a formal connection between God and redeemed humanity, initiating a new beginning where the legacy of Adam's sin is left behind.

Mary holds a significant role as the mother of Jesus Christ, largely due to her willing acceptance of this extraordinary responsibility. Her faith, demonstrated through her love, enabled the incarnation of the divine Word, which is fundamental for humanity's redemption and the dissemination of divine grace. This grace is essential for personal regeneration and justification before God. As the one who brought the source of all grace into the world, Mary continues to serve as an essential mediator. She is often referred to as the "neck" that connects Christ (the Head) to the members of His Mystical Body, as highlighted by St. John Damascene (De Nativitate Virginis). In this capacity, she plays a vital role in distributing divine graces originating from her Son.

In the accounts of Jesus’ miracles, it is notable that none were performed at the request of the apostles, even during significant events like the marriage feast in Cana. Instead, it was Mary, His mother, who approached Jesus with the expectation of a miracle. Unlike the apostles, who once suggested sending the hungry crowds away (Mt 14:15-21), Mary did not advocate for the end of the wedding festivities. Recognizing the need, she instructed the servants to follow whatever Jesus would command. Importantly, Mary did not directly address the bridegroom regarding the wine shortage, even though it was his duty to ensure an adequate supply for the week-long celebration. Her statement, “They have no wine,” reflects her confidence in Jesus as the awaited Bridegroom, prophesied to bring forth the wine of salvation for the redemption of Israel and humanity. The “best wine” that Jesus provided, flowing abundantly, echoes the promises made by the Hebrew prophets.

All unmerited graces are believed to originate from Christ, who is seen as the Head of His Mystical Body. These graces, however, are said to flow through Mary, often referred to as the neck of the body. This relationship emphasizes that, particularly for the sake of His mother and due to His perfect love for her, Christ imparts significant graces to humanity, even considering our unworthiness. An example of this can be found in John’s allegorical account of the wedding feast, which illustrates the special connection between Mary and Jesus in the distribution and application of divine grace in our lives. As our spiritual mother, Mary is recognized for having conceived and given birth to Jesus, allowing us to be spiritually reborn and enjoy a renewed relationship with God. Consequently, the Church has designated Mary as the New Eve, emphasizing her pivotal role in Christ's redemptive work. Jesus transformed water from six stone jars, typically used for ritual purification, into over one hundred gallons of wine. This act is significant in its symbolism, as represented in John’s First Epistle (5:6), where it is noted that Jesus entered the world “not by water only” but “by water and blood,” emphasizing His dual nature and mission.

Mary is often referred to as the second Eve, and in this role, she is considered the Mother of the Church. This title reflects her importance in the symbolic representation of Mother Zion, where the Church embodies the sacrament of grace for all humanity. In this context, the heavenly sanctuary is where the Lamb of God continuously intercedes for us through the merits of his precious blood. The grace that He offers, stemming from His infinite merits, is primarily conveyed through our Blessed Mother. Her mediation serves to formally unite us with Christ, our Divine Bridegroom.

May he send you help from the sanctuary,

and give you support from Zion.

Psalm 20, 2

In the Gospel of John, the author illustrates a profound connection between Mary and Eve, portraying Mary as the spiritual "mother of all the living" in her relationship with Jesus, the New Adam, as his “helpmate” (Gen 2:18). The Hebrew word for “helpmate” or “helper” is ezer, which can also mean “rescuer” or “strength.” This suggests that Eve was not merely a subordinate assistant but a powerful and equal partner. This thematic representation is evident in the structure of the Gospel, which begins with a narrative reminiscent of the creation story found in Genesis 1. The Evangelist employs a seven-day framework that mirrors the original creation, ultimately leading to the initiation of Jesus’ public ministry, which is intricately linked to the theme of redemption from the sins of Adam and Eve. Significantly, John’s Gospel presents a ‘New Creation’ narrative, highlighting the collaboration between the new Adam and his counterpart, the new Eve, as they work together to restore the fruit of life and overcome the consequences of the Fall.

Day 1

That was from the beginning, that which we have heard,

which we have seen with our eyes;

that which we contemplated,

and our hands handled,

concerning the word of life;

John 1, 1

Day 2

The next day, John saw Jesus coming to him,

and he saith: Behold the Lamb of God, behold

him who taketh away the sin of the world.

John 1, 29

Day 3

The next day again John stood, and two of his disciples.

And beholding Jesus walking, he saith: Behold the Lamb of God.

When the two disciples heard him say this,

they followed Jesus.

John 1, 35-36

Day 4

On the following day, he would go forth into Galilee, and he findeth Philip.

And Jesus saith to him: Follow me… Jesus saw Nathanael coming to him:

and he saith of him: Behold an Israelite indeed, in whom there is no guile.

John 1, 43-44

Day 5

The next day John saw Jesus coming toward him and said,

“Look, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!

John 1, 29

Day 6

The next day John was there again with two of his disciples.

When he saw Jesus passing by, he said, “Look, the Lamb of God!”

John 1, 35-36

Day 7

The next day Jesus decided to leave for Galilee.

Finding Philip, he said to him, “Follow me.”

John 1,43

Jesus is journeying to Cana in Galilee, while John continues to baptize people in the Jordan, many of whom will follow Jesus and have the light of life through the regenerating baptismal water: men and women of every kind, the great and the small alike. Up to three thousand people were baptized on the first Pentecost Sunday (Acts 2:41). The second creation story begins in Chapter 2 of John’s Gospel with the marriage feast in Cana attended by the New Adam (Jesus) and his helpmate the New Eve (Mary) present there with him.

The wine mourns, the vine languishes, all the merry-hearted sigh…

No more do they drink wine with singing…

There is an outcry in the streets for lack of wine;

all joy has reached its eventide; the gladness of the earth is banished.

Isaiah 24, 7, 9, 11

On this mountain (Zion), the Lord Almighty will prepare a feast of rich food for all

peoples, a feast of fat things, a banquet of aged wine – of fat things full of marrow, of

fine wine well refined. And he will destroy on this mountain the covering that is cast over

all peoples, the covering that is cast over all nations. He will swallow up death forever,

and the Lord God will wipe away tears from all faces, and the reproach of his people he

will take away from all the earth.

Isaiah 25, 6-8

AND the third day, there was a marriage in Cana of Galilee: and the mother of Jesus

was there. And Jesus also was invited, and his disciples, to the marriage.

John 2, 1-2

.And I heard as it were the voice of a great multitude, and as the voice of many waters, and as the

voice of great thunders, saying, alleluia: for the Lord our God the Almighty hath reigned. Let us

be glad and rejoice, and give glory to him; for the marriage of the Lamb is come, and his wife hath

prepared herself. And it is granted to her that she should clothe herself with fine linen, glittering

and white. For the fine linen are the justifications of saints. And he said to me: Write: Blessed

are they that are called to the marriage supper of the Lamb. And he saith to me: These words of

God are true.

Revelation 19, 6-9

In St. John’s account of the new creation, the narrative reaches a significant point during the wedding feast at Cana. This event takes place on the seventh day, symbolizing not a day of rest for Jesus, but the beginning of His salvific mission. This story can be interpreted as a second creation narrative, with Jesus representing the New Adam and Mary serving as the New Eve. The account is rich in literary and theological symbolism. The first miracle performed by Jesus occurs at the request of His mother and involves transforming water into wine. This act parallels Moses’ initial miracle, where he turned water into blood. In the Cana narrative, the water is transformed into wine, which is described as the “blood of the grape” in Genesis 49. This imagery implies that Jesus is foreshadowing the conversion of wine into His blood during the Last Supper, which is understood as the sacrificial New Passover meal leading to the heavenly wedding banquet.

On the second day of the new creation, John the Baptist encountered Jesus and declared, “Behold the Lamb of God, behold him who takes away the world’s sin” (Jn. 1:29). In John 2, this Lamb of God participates in a wedding feast accompanied by his mother and disciples. This wedding feast serves as a representation of the eschatological wedding banquet of the Lamb, a concept that John elaborates on in the book of Revelation. The events that unfold at the wedding in Cana find their ultimate fulfillment in the New Jerusalem, which descends from heaven (Rev. 21:1-5). This intangible reality is made tangible through the sacrament of the Holy Eucharist, which is celebrated during Holy Mass. The Mass acts as a re-presentation of Calvary and has been part of the practices of the Catholic Church since the time of the Apostles (1 Cor. 10:16).

The Gospel writer emphasizes a deeper divine mystery that goes beyond what is immediately apparent. He highlights the role of Mary and crafts her interaction with Jesus to showcase their significant connection to the divine work of salvation. Mary’s presence at the wedding feast, alongside her Son, is intentionally designed, much like the angel Gabriel’s announcement to Mary in the Gospel of Luke. In the Scriptures, every detail holds purpose; nothing is incidental. By the time this Gospel was composed, a rich Marian tradition had already developed within the early Church. Through the intercession of Mary, who is recognized as the faithful Mother, the blessings of her Son are made accessible to believers. At the wedding feast of the Lamb, Mary, as the mother of the Son, symbolically presents Him as the groom to the Church, which acts as the bride and serves as a sacrament of divine grace for all humanity (Revelation 21:1-2, 9-22).

It is noteworthy that Mary did not approach the bridegroom directly when the wine ran out at the wedding feast. This situation can be understood through the lens of ancient Judaic traditions. Mary was likely aware of the prophetic teachings that expressed Israel's yearning for the "wine," symbolizing the Messianic wedding. This wine represented the fulfillment of the marriage covenant between God and Israel and was an offering made by people from various nations at the Temple on Mount Zion. By bringing this issue to her son, Mary acknowledged his role as the Messiah, who would ultimately fulfill this long-awaited prophecy.

The Jews have long anticipated a banquet that would be inclusive for both Israel and the Gentile nations, envisioned as a sacrificial wedding banquet featuring wine. The prophet Isaiah refers to "fat things" and "fine wines," which symbolize the offerings made to God—both bloody and unbloody sacrifices—within the Jewish Temple (see Leviticus 3:16; 23:13). This wedding banquet, to be hosted by the Messiah, is believed to have the power to reverse the consequences of the original sin committed by Adam and Eve. It is foretold that this event will "destroy the covering that is cast over all peoples" and "swallow up death forever." Additionally, God will "wipe away tears from all faces" and remove the reproach of His people from the earth.

During the time of Jesus and his mother Mary, Jewish beliefs held that an eschatological wedding banquet would symbolize the fulfillment of the spiritual marriage covenant between YHWH (God) and Israel, encompassing all nations. This banquet was seen as a return to the Garden of Eden, representing a time before the fall of Adam and Eve. It was believed that the righteous would partake of miraculous wine and experience the Beatific Vision of God during this event. When Mary remarked, “They have no wine,” she was expressing the Jewish hope for the wine that would be provided by the Bridegroom YHWH at His banquet, symbolizing the wine of salvation. Her statement indicated that the finest wine, saved for last, was represented in the transformed form of her divine Son’s blood, as referenced in John 2:10.

Mary, much like John the Baptist, recognized that her son was the Lamb of God, destined to take away the world's sins through his selfless act of sacrifice. By making her request, she subtly indicated her hope that he would provide the prophetic sacrificial wine of salvation, which the Jewish people had long awaited. Traditionally, the Jews anticipated that YHWH would send a Messiah to lead the offering of unbloody sacrifices of bread and wine for the forgiveness of sins on Mount Zion. However, they did not foresee that this celebration would ultimately manifest as the holy sacrifice of the Mass within the Catholic Church, referred to as the New Jerusalem—a visible representation of the invisible heavenly marriage banquet at the end of this age. In this sacrificial context, the bread and wine, offered by Christ as our High Priest in the order of Melchizedek, become the true substance of His body and blood, presented in a form recognizable to humanity.

Our Lady of the Holy Eucharist

Mary understood that the sacrificial victim would be the Divine Groom Himself, in the person of her Son, Jesus, by the outpouring of His blood —the wine of the new and everlasting covenant. His bride would be a redeemed humanity and His Church. The Groom’s gift to his bride would be the giving of himself in his sacrificial act of love: the regenerating water and justifying blood that poured out from his pierced side upon the consummation of their eternal marriage covenant (Jn. 19:28-35). On this occasion, a sword would also pierce Mary’s soul (Lk. 2:34-35). Therefore, Mary approached Jesus as she would have the bridegroom of the wedding feast at Cana, who was responsible for providing the wine. Mary did not expect her Son to sacrifice himself at the wedding feast, but she understood that it was time for him to begin his public ministry in the shadow of his self-immolation for the forgiveness of sins. Our Lord knew that his mother knew (what to thee and to me), and so he told her these comforting words: “My hour has not yet come.”

The Last Supper, also referred to as the sacrificial wedding banquet, is significant in Christian theology, as it is believed to represent the forthcoming culmination of the relationship between God and humanity. According to interpretations, Jesus indicated to his mother that this event was still three years in the future, coinciding with his crucifixion, which is seen as the consummation of this divine marriage. This pivotal moment occurred when Jesus accepted the sour wine offered to him on a hyssop branch, symbolizing the fourth Hallel cup, known as the Cup of Consummation, which is traditionally included at the end of a Passover meal but was notably absent during the Last Supper, as depicted in the Gospel narratives (John 19:28-30).

At the wedding in Cana, the guests were provided with wine, but this act also symbolized the arrival of the Divine Bridegroom, who was expected to host the sacrificial banquet of salvation and establish a new covenant with humanity. This action fulfilled various prophecies regarding redemption. In this context, when Mary, the mother of Jesus, urged him to address the lack of wine at the wedding by stating, “They have no wine,” she was essentially requesting him to reveal his identity as the long-awaited Divine Bridegroom and to provide the metaphorical "wine of salvation," representing his own blood for the redemption of humanity.

Mary is regarded as the spiritual mother of all humanity due to her role as the mother of Jesus. It is believed that she played a crucial role in prompting Jesus to provide the "wine of salvation," which serves to rectify the sin of Adam and enables humanity's return to the Garden of Eden. In addition to her maternal role, Mary is seen as the universal Mediatrix of Grace, a figure responsible for distributing actual graces that assist individuals in their spiritual growth. Her Assumption into Heaven, which encompasses both body and soul, further enhances her maternal responsibilities. Through the body and blood of Christ, which she embodies, her followers can strive for spiritual growth and pursue perfection on their journey toward heaven and the eternal celebration of the wedding feast of the Lamb.

“Arise, my darling,

my beautiful one, come with me.

See! The winter is past;

the rains are over and gone.

Flowers appear on the earth,

the time for pruning the vines has come,

and the song of the dove is heard in our land.

The fig tree puts forth its figs,

and the vines, in bloom, give forth fragrance.

Arise, my beloved, my beautiful one,

and come!

Song of Solomon 2, 10-13

Early Sacred Tradition

St. Ephraem of Syria (A.D. 373)

“With the Mediator you are the Mediatrix of all the world.”

St. Theoteknos of Livias (ante A.D. 560)

“Raised to heaven, she remains for the human race an unconquerable

rampart, interceding for us before her Son and God.”

St. Germanus of Constantinople (ante A.D. 733)

“Mary the Ever-Virgin — radiant with divine light and full of grace,

mediatrix first through her supernatural birth and now because of the

intercession of her maternal assistance — be crowned with never-ending

blessings …seeking balance and fittingness in all things, we should make

our way honestly, as sons of light.”

St. Andrew of Crete (ante A.D. 740)

“O, how marvelous it is! She acts as a mediatrix between the loftiness of God

and the lowliness of the flesh, and becomes Mother of the Creator.”

St. John Damascene (A.D. 749)

“From her we have harvested the grape of life;

from her we have harvested the seed of immortality.

For our sake, she became Mediatrix of all blessings;

in her God became man, and man became God.”

AVE MARIA

Create Your Own Website With Webador